Character Tropes, Red Velvet Ropes

May 31, 2021

Wrapped in a fuzzy blanket with a bowl of buttered popcorn on his lap, a 10-year-old Tom Baker ’22 snuggled alongside his parents as they shuffled through films on their family movie night. From animated Pixar films to action-packed pirate adventures, Baker’s family filled his childhood with vivid stories––most of which hinged on male-female romances.

As an LGBTQ student, Baker said he did not feel embodied in the content he saw and often felt different because of the lack of on-screen LGBTQ representation.

“Later in life, having seen actual queer representation in media, I know how helpful it is and how much it actually speeds up your developmental process,” Baker said. “When you’re younger, you’re not really choosing what movies you’re watching, so it’s always just a man and a woman, always, every single movie. So when you’re conditioned into that, it just programs into your head that who you are is not normal, but it fully is.”

Since he became more secure in his identity, Baker said he has been more selective with the media he watches and seeks out LGBTQ representation that makes him feel seen on screen.

“I am more of a fully realized person, and I realize my identity and then choose to reflect that in what I watch,” Baker said. “I choose to watch a lot of shows or movies that have queer representation because that’s what I’m drawn to. [It is] what I can relate to, and that’s what I enjoy watching.”

Gender and Sexuality Awareness (GSA) Club leader Felicity Phelan ’21 said LGBTQ stories can be critical in the lives of young queer people who are in the process of self-discovery.

“When you’re really young, depending on what environment you’re growing up in, it’s possible that media representation is the only time you’re even hearing about LGBTQ identities,” Phelan said. “From that perspective, I think it’s a really valuable way that young LGBTQ kids are able to find themselves or realize that things they might be feeling are not just them and are experienced by other people.”

Upper School Video Art Teacher and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Coordinator Reb Limerick said they felt the impacts of LGBTQ presence in media growing up. Limerick said that while watching Olivia Wilde’s character, Alex Kelly, on “The O.C.” in high school, they felt connected to their own experiences and self-exploration.

“I liked that [Kelly’s queer relationship] wasn’t treated as a lesbian phase, but rather that both characters identified as bisexual and liked all genders,” Limerick said. “I just remember that being something that opened my eyes and mind: that if I was attracted to girls in high school, it didn’t necessarily mean I was a lesbian and that I could also be bisexual or pansexual. So just seeing that as a part of the storyline on ‘The O.C.’ definitely made me question my own sexuality in a way that felt safe.”

Phelan said seeing queer archetypes amid the plethora of typical high school stereotypes in “Mean Girls” helped normalize the prospect of being queer for them.

“I remember seeing Janis Ian in ‘Mean Girls,’ and even though she isn’t a lesbian, for much of the movie, she’s presented as a lesbian character, and just hearing that word and seeing her aesthetic, unattached to sexuality, was a moment of realization for me,” Phelan said. “To see that as a possibility for a younger person, even a high schooler, was important to me.”

Baker said an example of a queer archetype he regularly sees is the ‘gay best friend,’ prominently used as a tool of comedic relief in place of developed queer representation. Baker said he often feels he does not fit into the ‘gay best friend’ trope he sees in film and television and that feeling separated from this stereotype has left him questioning if he is doing something wrong.

“I think tropes are kind of harmful because, in a way, they dehumanize [queer characters],” Baker said. “It puts people into a sort of box. It’s so hurtful to have these different labels and boxes that people feel like they have to be forced into, and if they don’t fit into these boxes, they’re not validated by [the] media.”

Similarly to Baker, Avery Konwiser ’22 said he feels misrepresented by LGBTQ archetypes. Konwiser said he understands that they leave many queer teenagers believing they need to change.

“I find that queer people tend to be portrayed in broad archetypes, and I personally don’t think that I really fit into those archetypes because everybody’s different,” Konwiser said. “Archetypes can be very limiting to queer people whose only exposure to LGBTQ people in media are those very specific tropes, so I think people might feel very restricted and [think] that, ‘I’m not this kind of specific person. That means people won’t accept me, and I should change how I’m perceived or who I am.’”

Phelan said they recognize that for those who do not fit the molds cast by media archetypes, watching these stereotypical portrayals of LGBTQ characters can be destructive. However, Phelan said stereotypical tropes can present realistic representations for audiences who can relate to them.

“I think a stereotype is a stereotype, and it can be harmful for people and can build up expectations in people’s minds,” Phelan said. “But if you are someone who aligns with that stereotype, it can be [representative]. This representation shouldn’t be the only representation that we see of LGBTQ identities, but we shouldn’t strike it all from the books just because it’s stereotypical.”

Even with the prevalence of LGBTQ tropes, Konwiser said he has seen an increase in queer representation lately, which he believes is a shift from the historical tokenization of LGBTQ characters in media.

“Just the fact that there are more queer people in media is helpful and eye-opening,” Konswiser said. “You used to have [television] shows in the 90s and 2000s where a single gay character was out-of-the-norm, and that character was a sort of token. But having the expansion of inclusion of queer people in media is something that’s good and, in recent years, has seen a rise.”

Phelan said they’ve seen a lack of intersectionality when it comes to diversity, queer characters and their stories and that they hope this will change in the future.

“I would say, recently, we’re getting more queer characters of color,” Phelan said. “But in order for it to be ‘more,’ this has to speak to the fact that for [a long time], they’ve been very white stories.”

Phelan said having diversity and LGBTQ representation off screen is just as essential as having on-screen portrayals and that authentic representation leads to more genuine media representation.

“I think people telling stories that draw from their own lives are going to make more raw or impactful or emotional art than people going off of what they think it’s like to be a certain identity,” Phelan said. “So I definitely think giving creators the opportunity to share their own stories is important—one, because it’s good to give those people opportunities, and two, because I do just think it makes more real and accurate art.”

Limerick said having characters that represent them in both the plot of the story and off-screen feels significant when connecting with characters.

“A modern example that’s been groundbreaking for me has been seeing Alex Newell on ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist,’ who is gender nonconforming, and the character that they play is gender-fluid,” Limerick said. “Mo, the character on ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist,’ as well as [Newell], both go by all pronouns, similar to how I identify.”

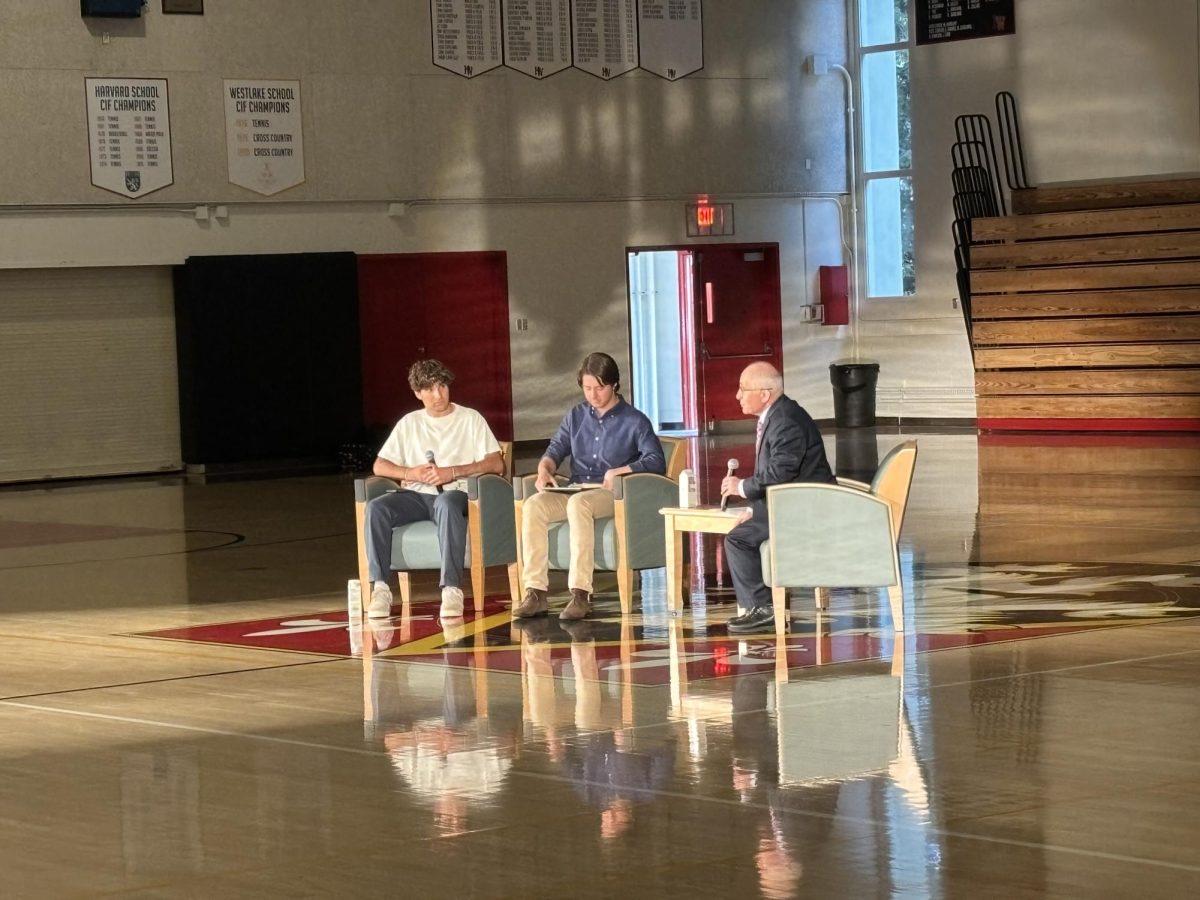

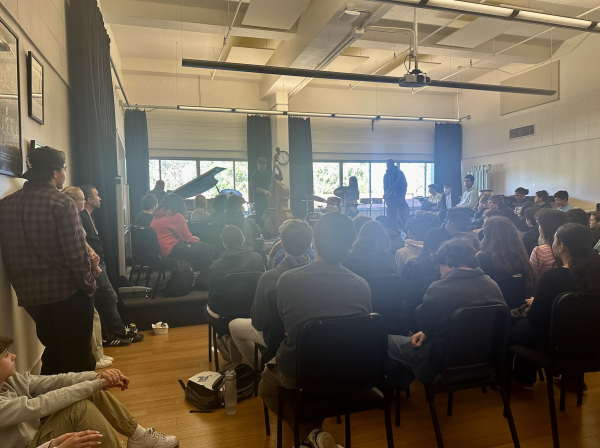

In a Community Flex Time webinar hosted by GSA Club on May 14, actress Hunter Schafer discussed her experiences growing up as a transgender person and recalled how seeing LGBTQ representation in the media played a role in defining her. After working as a model for several years with brands such as Calvin Klein and Versace, Schafer secured the role of Jules Vaughn on HBO’s “Euphoria” and had the opportunity to represent a transgender character on-screen as a transgender actress herself. Schafer said she feels meaningful LGBTQ representation is crucial because it humanizes queer people for those who may not directly connect to the LGBTQ community.

“Growing up, if we, [LGBTQ people], had seen the kind of relationships, dynamics [and] gender expressions [that] we’ve all had to learn about through the internet or through exposure [from] other people who [we] might be surrounded [by, then we would] have easier access to [LGBTQ] communities,” Schafer said. “Media is really powerful in the sense that it can educate you not only on a surface-level sense with terminology, but also on an emotional level [so that whoever] you’re watching, you create an emotional bond with.”